Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan became the first to utilize a new ethics principle that indicates justices may explain why they are recusing themselves from a case.

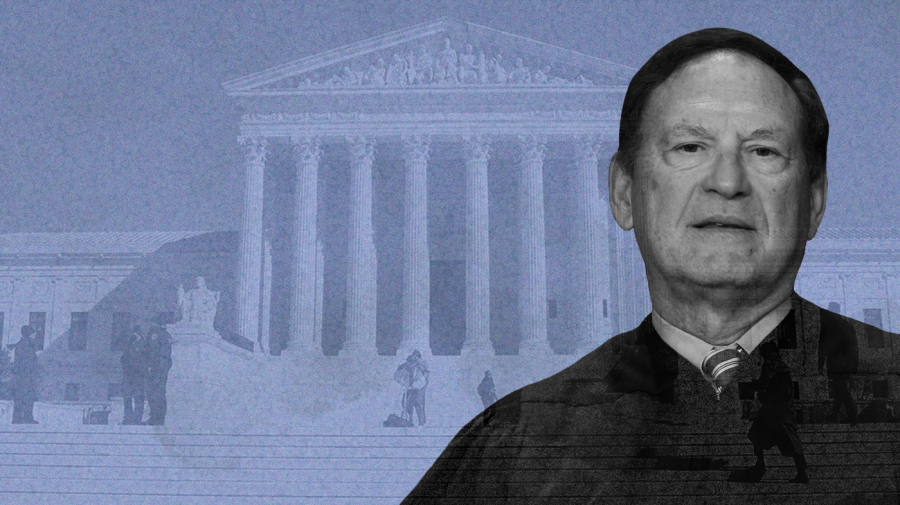

But her conservative colleague on the bench, Justice Samuel Alito, opted not to share why he was stepping aside from a separate case, raising questions about whether the court can reach a consensus on its ethics standards, which have been under heavy scrutiny.

“It really ought to be the direction the court goes, because at a time when there’s increasing skepticism, it’s one damned scandal after another, one way of dealing with that is through a little bit more transparency,” said Charles Geyh, a professor at the Indiana University Maurer School of Law.

The cases couldn’t be more different. Kagan recused herself from a matter involving a death row inmate, citing previous government employment; she served as U.S. solicitor general in the Obama administration.

Alito opted to recuse himself from a case involving energy companies. While he provided no explanation on the matter, his financial disclosures show he owns stock in one of the companies involved in the case.

The different approaches by Kagan and Alito have now become a subject of conversation for court watchers who think there should be a standard for justices to explain to the public the reasons behind a recusal.

In the wake of ProPublica’s reporting about undisclosed luxury trips that Justice Clarence Thomas accepted from Republican megadonor and real estate developer Harlan Crow, Democrats and judicial watchdog groups renewed a push for the justices to adopt a binding code of ethics.

Weeks later, all nine justices signed and released a new statement on ethics that indicates a justice “may provide a summary explanation of a recusal decision.”

Since the statement, justices have noted recusals 11 times, according to court records. Kagan became the first to leverage the new option to share her reason, and Alito is the only one since her to have recused but without giving a reason.

“I don’t fault Justice Alito for failing to include a reason for his disqualification, because I think that’s just been the norm. But I do applaud Justice Kagan for offering an explanation,” Geyh said.

Recusals at the high court are commonplace and occur roughly 200 times per year between all nine justices, according to the court. But research by watchdog group Fix the Court suggests Kagan’s recent choice marked the first time in 99 years that a justice gave an explanation.

Her note was brief, citing “prior government employment” without further detail. The inmate who was petitioning the Supreme Court had also done so years earlier, while Kagan was serving as U.S. solicitor general.

Days later, Alito gave no rationale for his recusal. But it appears to have been the result of a personal financial interest.

The justice’s most recent disclosure indicates he invests in Phillips 66, one of the parties in the case, and the justice recently recused himself from another case involving the energy company.

Alito did not return a request for comment through the court’s public information office.

Legal ethics experts said both are common reasons for recusals, but they are closely monitoring if any others follow Kagan’s lead.

“It may turn out to be just a practice that Kagan does by herself, and you’ll get to a particular behavioral trait that characterizes her and none of the others,” said Russell Wheeler, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Democrats have meanwhile called for an outside intervention, arguing the court can’t be trusted to police its own ethics after the recent woes.

Chief Justice John Roberts has brushed aside those calls, and last week he stressed that he was “committed” to ensuring the court adheres to the highest standard of conduct, but signaled that was an insular process.

Each justice largely maintains autonomy in making recusal and other ethics calls.

“The question becomes, are there alternative means to deal with Supreme Court recusals other than just leave it up to the judge, which some people say violates the old maxim that judges should not be judged in their own case?” Wheeler said.

The Supreme Court is also different from other federal benches, where an individual judge doesn’t hear every case that comes through their court.

A justice’s recusal, however, changes the voting math. The court’s recent statement cautions that explaining is “ill-advised” in some circumstances, including when it might encourage strategic behavior by lawyers in future cases to prompt a recusal.

Before the new policy, justices generally only provided explanations when declining a party’s request for them to recuse themselves from a case.

Roughly two decades ago, Justice Antonin Scalia issued such a memo when he rebuffed calls to recuse himself from a case involving former Vice President Dick Cheney following the duo’s duck-hunting trip, which came three weeks after the justices agreed to hear the case.

“If it is reasonable to think that a Supreme Court Justice can be bought so cheap, the Nation is in deeper trouble than I had imagined,” he added.

Scalia’s multi-page memo was far more extensive than the brief explanations the justices may now start issuing, but the effect may remain the same.

“That has served as precedent. In other words, if you’re going to treat as precedential when you don’t disqualify, then why not when you do?” Geyh said.