It’s being used by Democrats to influence the course of elections

I have been thinking about the phrase “the fix was in.” What it means is that a certain result was predetermined. It carries with it a suggestion — but only, I think, a suggestion — of something, if not quite illicit, then at least not quite above board.

Why have I been thinking about that pregnant phrase? If you said “the midterm elections,” go to the head of the class.

I have no idea whether there was anything corrupt or underhanded about the election, notwithstanding the Caligula’s horse moment of John Fetterman’s election to the United States Senate. It was odd, no doubt, that the people of the great state of Pennsylvania elected a mentally incompetent trust-fund leftie who never saw a dead baby he didn’t like. But perhaps, like Caligula, who is said to have made his horse a consul, the people of Pennsylvania did it out of spite, just to show that they could. Or maybe Fetterman’s elevation to the 100 club is just an illustration of the old observation that anybody — and I mean anybody — can rise to the top in America.

Of course, by “anybody,” I do not mean “anybody.” I mean anybody with the approved left-wing attitudes.

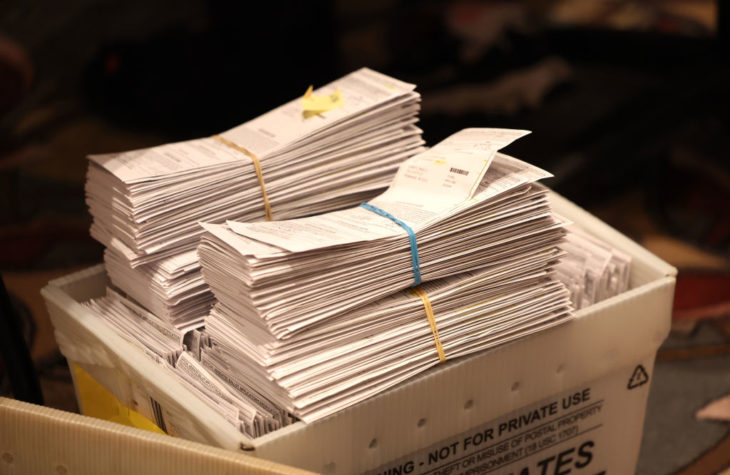

But I digress. Let’s return to that “fix” I mentioned above. What was the determinative fix in the 2022 midterm elections? Early, mostly mail-in, voting. It is perfectly legal. But it undermines a fair and open electoral process. Were I a Democrat, I might even say that it “threatens our democracy.” Why? Because it allows for the wholesale manipulation of the vote. It also dilutes the integrity of an election by transforming it from an event into a process.

I should add that “mail-in ballots” is an equivocal term. It can mean different things in different contexts and in different states. The practice is obviously open to more interference and manipulation than same-day voting is. So extra safeguards must be put in place and scrupulously followed if such interference and manipulation is to be avoided. Some states do this. Florida is a good example. Other states do not. Apparently, about 1.4 million people asked for mail-in ballots in Pennsylvania. Around the same number voted early by mail in Arizona, compared to just shy of half a million on Election Day. Were all such ballots carefully checked to ascertain the identity and eligibility of the person casting the vote?

I doubt it, but let’s leave that question to one side. The real issue is that the wholesale practice of early or mail-in voting makes a mockery of elections. If you say that an election is to be held on November 8, but millions of ballots are already docketed, if not actually counted, by the time November 8 rolls around, why bother to have Election Day at all? Why not have Election Week, or Election Month, or Election Quarter?

Elections are meant to represent a particular decision made at particular time at which voters can assess the state of things at that moment and make their choice. Early and mail-in voting undermines the definitiveness of that practice. I suspect that in many cases the result of an election is essentially predetermined by early and mail-in voting, something that makes the very idea of Election Day superfluous.

There is also the elephant, or rather the donkey, in the room: mail-in voting is largely a Democratic concession, encouraged and abetted by Democrats in order to help influence the course of elections. My own feeling is that the practice should be sharply curtailed, if not outlawed. If that is impossible, it should at least be made “safe, legal and rare,” as Bill Clinton said in another context.

I raised the idea of outlawing mail-in voting with a canny friend. “The Dems would never allow it,” he said, comparing the practice to nuclear weapons. Once they exist, it is impossible to get rid of them. Maybe so, in which case it behooves Republicans to become experts in organizing and deploying mail-in voting for their own candidates.

If nothing else, a little competition in the mail-in ballot sweepstakes would counter the invitation to corruption that follows on the feeling that the fix is in. In the election just past, it seemed, despite media forecasts of a red wave, that a certain complacency was abroad in and about the headquarters of certain contentious races. Gretchen Whitmer never seemed particularly worried about Tudor Dixon, nor did John Fetterman seem worried about Dr. Oz. Of course, Fetterman is a special case. But the point is, I believe, they knew that the fix was in and therefore — to employ another common idiom — that the race was in the bag.

By Roger Kimball

Roger Kimball is the editor and publisher of the New Criterion, publisher of Encounter Books and a Spectator columnist and contributing editor.