The document reveals the speed and scope with which agents can obtain information.

The DOJ/FBI has proven that they can’t be trusted to follow the law. The law enforcers are now the lawbreakers. Rep. Matt Gaetz: “The greatest domestic threat to America is the weaponization of the National Security State that has been directed inward against our own citizens, often for the preservation of corrupt institutions or the acquisition of political power.”

The FBI has the ability to see some of the contents of iMessage and collect metadata from WhatsApp in as little as 15 minutes, according to a recently published internal bureau document.

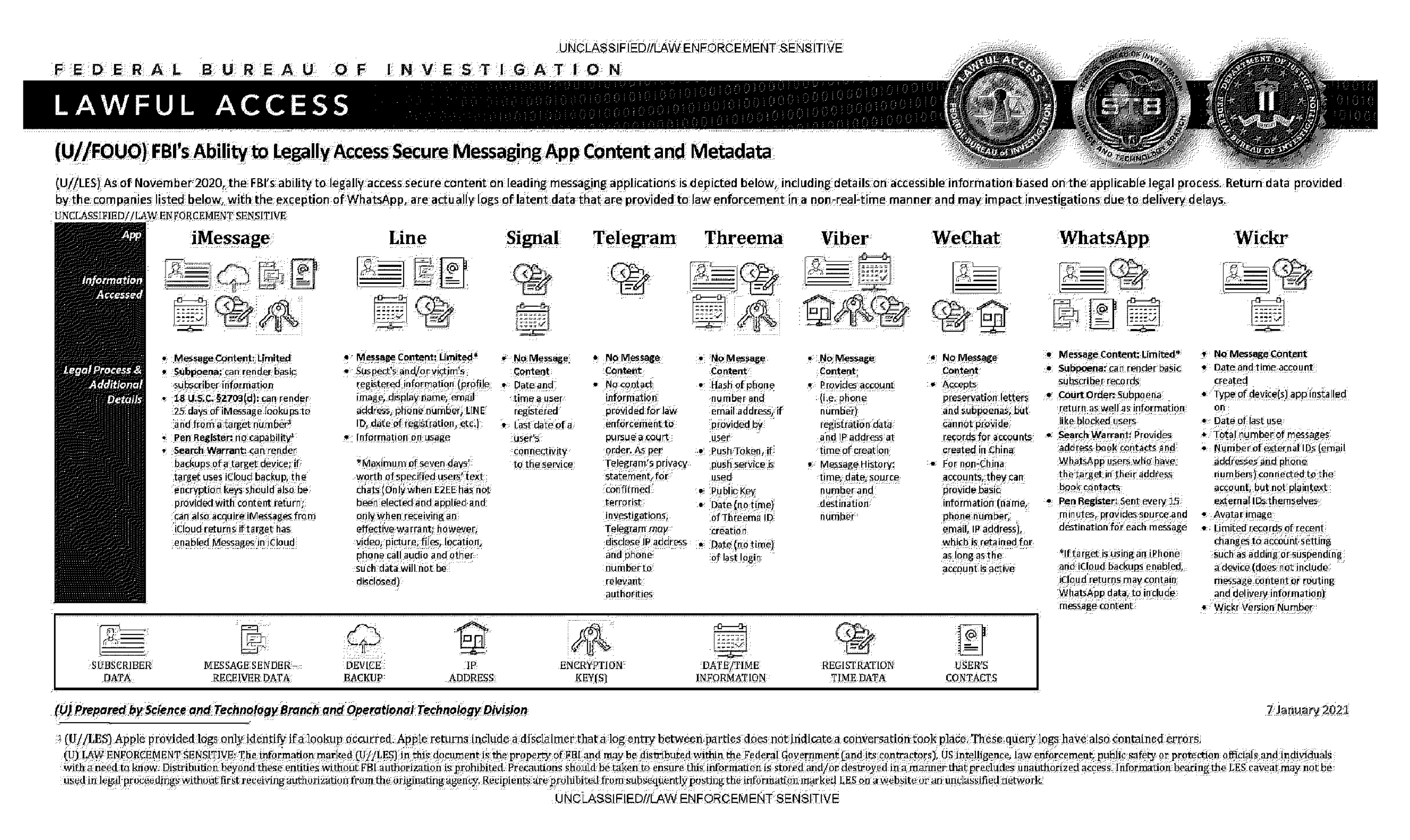

First published in November by nonprofit organization Property of the People following a Freedom of Information Act request, the document contains an infographic showing the FBI’s ability to lawfully access secure messaging app content and metadata.

While the FBI’s collection of messaging and call data has been well-known for years, the new document reveals the speed and scope with which agents can obtain such information—particularly with Facebook/Meta’s WhatsApp and Apple’s iMessage apps.

According to the document, WhatsApp provides the FBI with metadata every 15 minutes in response to a “pen register”—a surveillance request that provides the agency with the source and destination of each message for a targeted individual. Other messaging platforms—including iMessage, Signal, Telegram, and WeChat—provide logs of latent data, according to the document.

The document also states that the FBI can obtain “limited” content from iMessage. Apple encrypts iMessage, although not the backups for it in the cloud—unlike WhatsApp, which started offering encryption for backups in September.

“Search warrant can render backups of a targeted device,” the document reads. “If the target uses iCloud backup, the encryption keys should also be provided with content return; can also acquire iMessages from iCloud returns if the target has enabled iMessages in iCloud.”

The FBI also still can see the contents of backed-up WhatsApp messages if they’re unencrypted, which is the default setting.

Other platforms included in the FBI document include Signal, Telegram, and WeChat—none of which provide the content of messages to law enforcement. Chinese-owned WeChat accepts subpoenas for metadata but doesn’t provide records for accounts created in China, according to the FBI.

“For non-China accounts, they can provide basic information (name, phone number, email, IP address), which is retained for as long as the account is active,” the document reads.

The extent to which the FBI collects metadata isn’t clear. Facebook’s transparency center stated that the company received 63,657 law enforcement requests in the United States from January to June, but doesn’t distill the data further to show what agencies are making the requests.

Apple didn’t respond to an inquiry by press time.

After the document was published on Nov. 19, Facebook/Meta told Rolling Stone that the document “illustrates what we’ve been saying—that law enforcement doesn’t need to break end-to-end encryption to successfully investigate crimes.”

The FBI has long argued that end-to-end encrypted chat platforms hinder its investigations into a number of crimes, from ransomware to child pornography and domestic terrorism.

“I can’t overstate the impact of default encryption and the role it’s playing, including on terrorism,” FBI Director Christopher Wray said at a September congressional hearing. “The information that will allow us to separate the wheat from the chaff, in terms of social media, is being able to—with the lawful process—get access to those communications, where most of the meaningful discussions of the violence is occurring.”

During a Dec. 3 Livestream, technologists for the Freedom of the Press Foundation agreed with Facebook: The FBI’s access to messaging metadata should be enough for agents to be able to conduct investigations.

Whereas law enforcement could only usually collect a few data points on traditional calls—such as the phone numbers involved in the conversation—they can now collect troves of information on IP addresses, the port and protocols used, date, time, and location, according to the Freedom of the Press Foundation Chief Information Security Officer Harlo Holmes.

“Facebook is pretty much saying, ‘You have a couple of tools if you know how to use them,’” Holmes said. “Use data acquired via WhatsApp to pivot onto another legal request.”